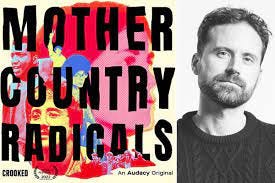

Q+A With Zayd Ayres Dohrn of Mother Country Radicals

Dig in to find out more about the podcast which is topping Best Of Lists for 2022

When I first heard this epic audio documentary/memoir last summer, I had a feeling it was going to create waves around it. The audio world finally has an A-List festival that pays attention to narrative podcasts, Tribeca, and Mother Country Radicals had already made a splash there last June.

Depending on who you speak to, the inclusion of podcasts by an institution like Tribeca is either the long-overdue recognition of audio storytelling as a sophisticated and innovative art form, or a heady endorsement of a medium that occasionally still struggles to shake off the perception of two men bro-ing out in front of a mic.

-Justine Goode, Vanity Fair “The Tribeca Festival Welcomes Podcasts

Into The Fold,” June 18, 2021 -

Tribeca audio storytelling works much like a film festival: The work must be a world premiere. Deadline is rolling, but final is February 22, 2023. Find out how to submit here.

This was the first series that Bingeworthy covered (read full review here), when I launched this publication last September, from a list of 0 … so I wanted to bring this back up to the top, and give it another shoutout, as most of the Best Of Lists for 2022 included this podcast in their top 10 for the year.

Mother Country Radicals is a memoir at the same time as it’s a history lesson.

But it also provides a schooling: on what America actually is; how it treated its radical sons and daughters; what role the government played; what the aims and the ambitions were of the group behind the sensational headlines; the acutely perceptible role privilege played; who died and how; and then what ultimately happened to the Radical Left, from the 1960s until it was more-or-less disbanded by the early 1980s.

This project could easily have descended into a narcissistic family history, but it manages to avoid that trap. It does this through balanced journalism, a trove of historical tape, a concise interview list…and it remains compelling because it’s told from Zayd’s personal perspective.

There are two perceptible questions that follow the entire series:

1 - Can bombs be a benign act of resistance…if they don’t aim to kill?

2- Where did all of that get them, and by extension, get us? And where to next?

The tone of the interviews conveys the kitchen table. It begins as an oral history, between a son and his mother.

But before the warm fuzzies settle in, remember that it’s also the same mother that spent years in jail after turning herself in from being on the FBI’s Most Wanted List…something that’s only been bestowed on just 11 women to date.

Despite the dark and difficult questions that Zayd asks, there’s a shorthand familiarity to it all, which gives it levity and bounce.

The following is an email interview between Samantha Hodder and Zayd Ayres Dohrn.

Samantha Hodder: You’ve written a lot of things…what was the spark that made you say: Now. Now is the time to tackle this project? Had you been sitting on this idea for a while?

Zayd Ayres Dohrn: I've been a writer for over a decade, but I never had the urge to tell my family's story in a nonfiction format. I wasn't sitting on it, I just felt I didn't have enough distance to shape it into a compelling or relevant narrative.

But there were two sparks that made me finally want to tackle it now - one was political, and one was personal.

The political side was the Trump administration and the rise of white Christian nationalism in America. I was thinking a lot about how to resist an out of control, authoritarian government. How ordinary people can fight back against racism and repression and police violence. And I realized that there was an important historical analogue - a recent period in American history during which young people, Black and white, came together to fight against white supremacy and police murdering Black people in America. And I had a unique window into that history. So that seemed like an important story to tell now.

The personal side was that my parents and their friends were all getting older - my mom had just turned 80. My adopted mom Kathy was dying of cancer. So I realized, if I was going to tell this story - in their voices - it had to be now.

SH: Does this exist as a book memoir as well? Wondering what the process was to begin storyboarding and then writing this narration. If it was already in book form, I can see how this could shortcut the experience. But it you were starting with the idea, that’s a whole other project plan.

ZAD: It was never a book. The project began as an oral history - I just wanted to ask my parents and their comrades these questions I'd been wondering about for years. So I was doing the interviews and imagining a narrative at the same time, really using the process of talking to people as part of the story itself.

SH: Who wrote the first draft of the narration, you or the producing team at Dustlight, or maybe Crooked?

ZAD: I wrote the narration - if I was going to say the words, it had to be in my voice. But we outlined everything as a team - my producers Ariana Lee and Stephanie Cohn, and our historical consultant Thai Jones - all worked with me to conduct interviews, gather archival audio, and draw up a blueprint for the story we wanted to tell.

It was a bit like being the showrunner in a TV writers room - a collaborative process with the four of us all contributing ideas, scenes, new material. And then an even larger team at Dustlight and Crooked Media giving notes, suggesting revisions, etc. I had final say on the text, but many many voices went into creating the show.

SH: What lessons did you bring from playwriting to podcast narration?

ZAD: As a playwright, I spend a lot of time thinking about story - about how narrative is built around character arcs - people in conflict forcing each other to change. I also think a lot about empathy, and about how an audience connects to characters who might at first seem unusual or unfamiliar, or even unlikable.

So my background as a playwright informed the storytelling in Mother Country Radicals in many ways; it's a history, but it's written as a character drama, and I wanted our audience to feel for these people who made unusual choices, and who may have made mistakes along the way, but who are ultimately connected to us by their recognizable flawed humanity.

SH: Which of the interviews DIDN’T you do? I ask because I assumed that you did all of them…until Chapter 6…when the producer Ariana Lee is featured in the episode, when she asks the FBI agent if he thought that, perhaps, their intimidation tactics went a step too far (eg putting your grandfather in a car pretending to take him to see the body of his daughter Bernardine).

ZAD: I did most of the interviewing, but there were certain people we felt might not be as open with me as they would be with an "objective" journalist. So, for example, Ariana Lee interviewed Special Agent Bill Dyson (and did a remarkable job of it). There were a handful of other interviews conducted by Ariana or Stephanie, usually because we decided they could have a more candid or honest conversation than I could with those particular subjects.

SH: Who did you pitch first? Who was the first YES? And then how did the rest of the publishing deal get pieced together?

ZAD: I never pitched the show. Sarah Geismer, the Head of Development at Crooked Media, called me and asked me if I wanted to do it. We had worked together in the TV development world so she knew my writing and knew some of my personal history. And she had the idea that it would make a good podcast.

SH: How long did all that take?

ZAD: About two years to write, produce, and release the series.

SH: What about the fact-checking process…wondering how that was tackled and who took on that responsibility? Did this require that each of your family members and friends essentially re-interviewed by someone? How did that play out?

ZAD: We had multiple rounds of fact-checking - our team did extensive research using primary and secondary sources to verify names, dates, places, etc. And we went back to everyone we interviewed at least once, often many times, in order to confirm memories and double check sources.

People didn't always agree on details, and sometimes people were unwilling to confirm certain things (like who committed certain crimes), and in those cases we acknowledged those contradictory recollections in the narration itself.

Ultimately, the fact-checking process took many months - I was involved in the process myself, as were our producers and editors, our historical consultant (who has a PhD and is an expert on the period), and an outside fact-checker.