Review of Sold A Story, Part 1

Decoding why two-thirds of American 4th Graders read below grade level

Emily Hanford has been researching and reporting on education for more than a decade…but it took the pandemic, and the forced closure of schools everywhere, for the penny to drop. That’s when the wider public, the mothers and fathers of young students, actually saw how school was being taught.

Now that “school” was taking place in the living room and kitchen table, parents had a new view of just exactly what their children were learning, and how. And in many cases, the results were shocking. Finally, the alarm bells that Hanford’s articles had been trying to sound for years, were being heard.

I should put a trigger warning in here…for anyone who has school-aged children and has endured virtual school during these last two+ years…this article might stir up some difficult emotions for you. For me, virtual school was fresh hell. My children are even old enough to navigate computers on their own. And still, it was, completely, truly, awful.

And the cold hard pill to swallow is that the pandemic has made all of the challenges of education even worse.

The statistics are well-documented and shocking; In the US, only one in three 4th Graders are proficient readers. This is not an alarmist statistic wanting to sell you something. It’s taken from the US Department of Education NAEP Reading Assessment in 2019. In 2022, the number fell further.

In Canada where I live, the numbers tell a similar story: 26 percent of all Grade 3 students did not meet the Provincial standard in 2019 (literacy tests are taken here in Grade 3 and Grade 6, not Grade 4 and Garde 8).

Hanford knows this well. She and her co-reporter Christopher Peak spent more than a year investigating, interviewing, researching, and asking questions to get to the answer of why.

Why has the issue of failing children been allowed to persist?

Why do we know we are VASTLY missing at the most basic job of education: teaching our children to read…and yet nothing has changed?

And perhaps more disturbingly:

Why is there a multi-billion dollar publishing empire that has been built off the backs of our children, whilst they have hoodwinked time-strapped teachers?

Why is this flawed system, based on pseudo-science, only just now being removed as the dominant education model?

This is where the story begins…two different parents in two different cities with two different economic backgrounds…who faced the same problem:

Neither of their children knew how to read well, nor read proficiently

One child was in Grade 1, the other in Grade 4.

Episode 2 dives into the idea that is woven throughout all levels of the education system, and it has informed curriculum development, in much of the English-speaking world since the 1970s.

And it’s such a simple idea that it might be easy to overlook its importance:

[Ep 2 6:50] Here’s the idea:

That beginning readers don’t have to sound out words.

They can, but they don’t have to,

because there are different ways to figure out

what the words say.

This was just that; an idea. But it was framed as science, based on observation. Decades later, when neuroscience had developed monitoring tools, we were able to monitor the brain to determine how our brain works when we read. That’s when this idea should have been relegated as bunk. But it wasn’t.

Starting in the 1960s

There were two competing methods of reading instruction:

Phonics instruction is the idea that you sound out words based on the syllables and repeating letter pairings. It begins with simple words that rhyme, and you gradually increase new words, and children will learn to sound them out.

Whole Word approach is based on the idea that you have high repetition in the words, which students memorize and become familiar with. If you keep adding to that list of words, offering bigger and bigger words, the vocabulary would grow as the list of memorized words grew. The popular book series used in schools at the time was called the Dick and Jane books.

A young Doctorate student named Mari Clay from New Zealand didn’t like either approach, and began her life’s work to find a third way.

Her new system would be called the:

Whole Language Approach which was rooted in the idea that you could introduce more words, with increasing complexity, even words that are tricky to understand, or difficult to sound out like a lamb and calf, because the underlying concept was that children could get meaning from the entire story, not just one word at a time.

The Whole Language Approach would also consider the pictures in the book, the other words on the page, and the greater meaning of the story. The concept is that young readers would put all these different clues to piece together the meaning, or the actual words, on the page.

It was also based on this core belief: that learning to read is a natural process, like learning to speak. That it happens spontaneously, from repeated exposure.

And it follows, then, that you can introduce more complex words and subjects to children, which will make them enjoy reading more, make it happen, faster and easier...because it’s natural.

A good part of this podcast series features the work and pedagogy of a New Zealand woman teacher-turned-academic named Marie Clay. She is not interviewed, as she passed away in 2007. The reporting does singularly point to her as the genesis of this theory, which spawned many books and copycat theories after her. There were others who had influence and did work like hers, but the reporting of this series clearly points to the connection and influence that Clay had with the US, through Ohio State University, as an advisor or lobbyist to George Bush I, and through various publishing enterprises, that began to grow in prominence in large school districts across the US.

As part of her doctorate work, Marie Clay began a study of her own. She had a cohort of 100 students in their first year of school in Auckland, New Zealand. She spent one year observing those children, some of whom were doing well, and some of whom were struggling.

Her analysis after spending a year observing these children would go on to influence public school curricula far and wide for decades to come. These 100 children, whoever they were, had a wide and lasting effect.

It would take decades, and some neuroscience, to realize that her conclusions were backward to reality, perhaps even actually anti-science. Learning to read, as neuroscience would later teach us, is not natural at all. And it doesn’t happen, outliers aside, without instruction.

Clay’s observation was that good readers were good problem solvers…and what she meant by that was that they would ask themselves a number of questions if they didn’t understand a word that they were trying to read; they would look to the picture for a clue, or the meaning of the story, or the other words on the page.

In essence, they would do everything, anything, except sound out the word in syllables, in order to figure out the word. They were, by in large, guessing, at what the word could be, by looking around the page. They would ask themselves questions like: Does it look right? Does it sound right? Does it fit what the picture depicts?

Clay determined that it was actually the poor readers who used letters to sound out the word, as an alternative approach.

Her defense of this was clear: In the English language, letters can be confusing. They’re don’t always they don’t always follow the same rules and the rules that exist are not uniformly applied.

Time, space and science aside, I can see some value in this. To understand whether or not the word is live or live, you must understand the meaning of the sentence:

Do you live here?

Is this live?

English is full of inconsistencies and when you’re learning grammar, at some point you realize that all the rules were made to be broken because there are so many exceptions.

I use this as an example because it’s from a similar place of logic that Marie Clay used to create her theory….it’s a casual relationship, an observation, an opinion. It’s many things, but it’s not science.

Clay said strong strong readers did not look at each of the letters in the words to understand what they were, they used other “cueing” strategies to piece it together. But in the 1980s, advances in neuroscience came where brain monitoring could track the eyeballs of readers, and then track how the neurons fire in the brain. It was determined with accuracy, that humans actually do process every letter in the word as they are reading. Neuroscience tells us that phonics is a natural learning process to follow for brains that processes one-letter-at-a-time.

Her theory, which then went on to create bigger systems inside of giant publishing empires, around how to help struggling readers, based on what she felt good readers did, was actually, exactly wrong. It was the bad readers who used cues, not good the good readers. They were, in effect, guessing, instead of using phonetic logic to sort it out.

This topic is so meaty that I’ve decided to spread it over two issues. This week I’ll include a portion of the email interview with Emily Hanford that answers some general questions about the show.

Next week we’ll dive into some more details, and also for the Canadians in the group, give some background on what’s happening in this country (including the unique learning system my children went through, which is French Immersion).

I’ll also open the discussion about the strange coincidence, of where George W Bush was, on the day that the Twin Towers fell. And what the ripple effect of that coincidence, and tragedy, was on the education system.

Samantha Hodder: You’ve been reporting on the subject of reading and kids and education for many years…what decisions led you to create a stand-alone investigative series? Did you pitch it, or did APM ask you to do this…in short, who saw that opportunity?

Emily Hanford: I guess I would say it was me who saw the opportunity/ the need to dig deeper into this topic with an investigative series. All of our work is supported by grants and for years we had funding to cover education - and education research - broadly. I first got interested in how kids learn to read – and how they are being taught – back in 2017 with an audio documentary about dyslexia (Hard to Read). Actually, it started even earlier than that with a project about so-called “remedial” ed in college (Stuck at Square One). (I walk through a bit of the story about how I got interested in the topic in this talk – start at about 12:30)

I had lots of questions about how it happened that many schools don’t teach reading in a way that aligns well with what is known about how people actually learn to read. The company and the authors that we focus on in Sold a Story came up all the time in my reporting – parents, teachers, all kinds of people – mentioned Reading Recovery and Fountas and Pinnell and Calkins and Heinemann. I’ve known for years there was a story there that needed investigating. I worked with development people at APM and our former editor-in-chief, Chris Worthington, to secure the funding to make it possible to get the time and the resources to do this. It took us more than two years. Longer than we thought. But we got the support we needed to make it happen.

SH: I feel like the show has a very specific pacing to it; the concepts are laid out clearly, and you signpost when you will mention something and then when you will circle back on it…tell me more about this process of writing the narration script. What iterations and drafts did you go through to get to the finished project?

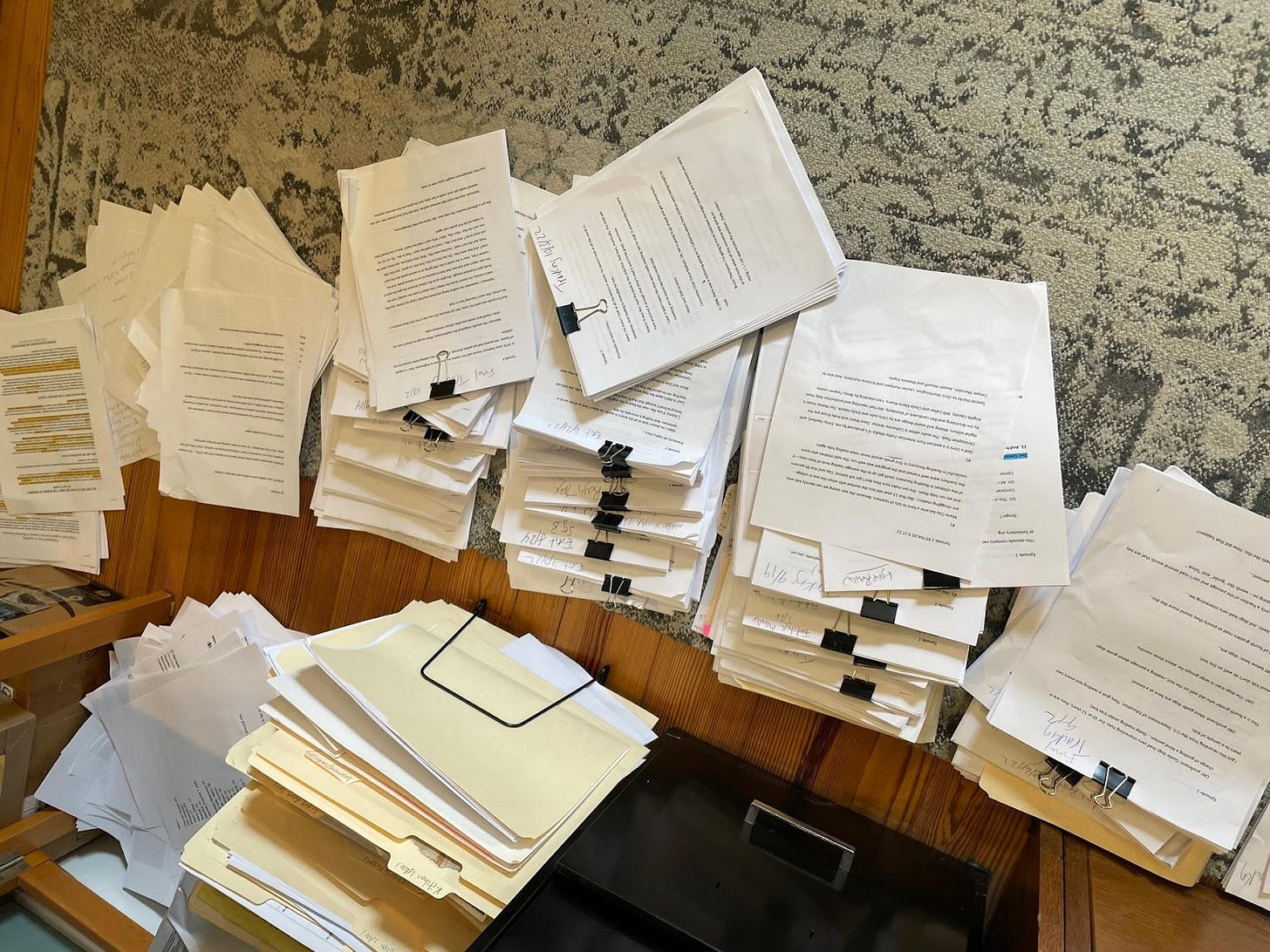

EH: Many iterations and many drafts!! Here’s what my office floor (still) looks like.

Each pile contains all the edits we went through on each episode – big restructuring and rewriting draft to draft.

I had a pretty good idea early on how the podcast would be structured in terms of what each episode would be about. I had it laid out in my mind as The Problem, The Idea, The Battle etc about a year ago. But actually structuring each episode, choosing how to tell each part of the story, was very hard and each episode went through many drafts. Entire storylines and characters were cut – and added – as I wrote and re-wrote and restructured. Our editor, Catherine Winter, played a huge role.

SH: There is no advertising on Sold a Story at all…in the credits you say that you have foundation money and some grants…I believe you are on staff at APM Reports, so was this treated as an in-house show? Was this your whole focus for some period of time, or an add-on to your regular beat and load?

EH: I am on staff at APM and have been since 2008. I was originally part of a documentary unit called American RadioWorks. ARW became part of APM Reports in 2015. APM Reports was the national documentary and investigative reporting team at APM. Unfortunately, that team was dissolved earlier this year; the idea is to continue with investigative reporting but with more of a focus on Minnesota. All of the former APM Reports staff who have not been laid off are now part of the Minnesota Public Radio newsroom.

I am still on staff at APM. I have been working on Sold a Story and related reporting since Fall 2020.

(We have all of our reporting on this topic collected here.)

See you next week with more Sold a Story!

If you haven’t listened to this series, yet, here’s the Apple link to listen to find it:

And then the Spotify link:

Series Details:

Sold a Story

American Public Media

6 Episodes

First published October 20, 2022

Release structure: October 20: Episodes 1 + 2, and then weekly

Final episode published November 17, 2022

Total Listening time: 4 hours, 8 minutes