Was 1938 Actually The Birth Of Narrative Podcasting?

Because War of the Worlds sure looked like one

Let me set the scene: It was the evening of 1938, the day before Halloween. Orsen Welles, the up-and-coming theater director, was just 23-years-old. That was the day that War of the Worlds was broadcast on CBS, on a live-to-broadcast CBS radio show called Mercury Theatre on the Air.

Welles was gunning for the cinema, where he would eventually make a name for himself (Citizen Kane). But cinema was new media at this point; radio was where you could get a steady job.

Until this point, he had been working on and off Broadway to make a name for himself. Earlier that year, Welles was given the chance to launch his audacious experiment; a show made by a sort-of ‘radio theater company’ that would adapt older literary works for live radio.

It was like so many podcast experiments of today: It was low-budget; it didn’t have a sponsor; it was an experimental form.

If you’re asking yourself: What’s a “live radio show?”

Let me attempt this…although I’m much too young to have experienced this myself, I’ve read and researched about it. In the early days of radio, networks would broadcast live performances of both music and drama. Radio stations employed ensembles, like a theater company. Actors, writers, musicians, producers, directors…they would all assemble in a radio studio, first to rehearse, and then perform, a show which was broadcasted live over the radio.

The actors organized around microphones, script on a music stand, each holding the sundry objects they might need to create foley sound effects (shoes, wooden blocks, bells, mallets, plastic to crinkle, etc).

The actors would read their part from a rehearsed script, the musicians often in the same room, and they would perform, for the vast radio audience. Television could also be live at this time, but they were very expensive machines. Not everyone could afford a television. Radio was accessible, everyone had one of those in 1938, which meant that the audience was much bigger for live radio than television.

The Director, who acted like an orchestra conductor, cued the different actors, sound effects, and bits of pre-recorded tape if that was being used, in the right moment. There was also a live orchestra, or paired down pit band. Together they performed live radio that was instantly broadcast to a hungry public, who gathered around their household radios much like we have been this past week for FIFA World Cup Soccer games.

Earlier that year, Orsen Wells had chosen the 1898 b-rate science fiction novel War of the Worlds, by H.G. Wells (no relation), to adapt for his show. The script had already been through multiple revisions.

The original novel War of the Worlds was a satirized story of an alien invasion of Britain, thought to be a scathing reference to colonialism. In America, the story had already been adapted and re-adapted so many times (it was now the “alien invasion format”) that it was a children’s science fiction novel, a comic strip...basically what we would call a “meme” of today….such as to say that it was a well-known format.

The premise of the Mercury Theater live radio version of War of the Worlds was that the aliens had invaded New Jersey, and the humans had to take cover. It was meant to be a joke, brought to life with all the poof and circumstance of live radio (which in this day, was the biggest mass audience a story could get).

Welles’ inner circle worried this was going to flop, so he brought in his screenwriter Howard Koch, writer for The Mercury Theatre On Air, to finish the job, while he was busy getting another Broadway show off the ground.

Here’s where it started: a kitschy novel that had been knocked off so many times it became a children’s science fiction comic strip. Here’s where it had to get to: to be adapted to fit the 1930s norms of ‘live’ radio.

Koch, and also Welles, did the same thing that modern-day podcasters have to do all the time:

Consider how to adapt something new within the context of an old medium, using a mixture of new and old tricks.

Koch knew that radio was good at delivering news. The convention at the time was for a singular male voice, the radio announcer, to read the news to the audience, often called a “bulletin,” in the present tense, which delivered an account of the happenings around the world.

Koch’s next decision was pivotal. He decided that the best way to get this story out into the world was to create “fake news” bulletins. He turned the script into a live news show, basically, a farse. This, he figured, would lull the audience through the incredulous parts, the aliens, and have some fun with it.

The joke was that this was actually happening. Koch thought it was so fake it would never be seen as “news,” but at least it would entertain.

Who would believe the stuff of a children’s sci-fi fantasy novel? He was more concerned that the audience was going to laugh and snicker and turn the radio off.

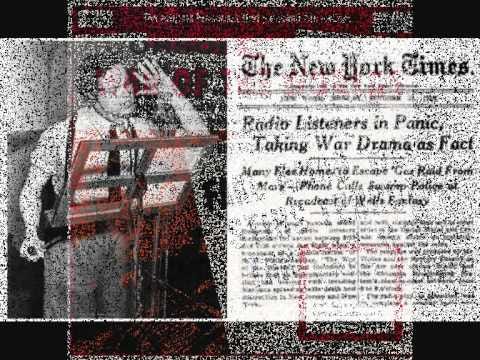

But that’s not how the audience reacted. All of those radio conventions used…the news bulletin, the “live” spots on the ground, the sound effects…but turned on their head…the audience missed this and took it as fact.

The aliens were indeed coming. War was beginning. The world was going to end.

And this created some very big problems. There was a concerned public. Some of them missed that it was “aliens” invading, and worried they were being….invaded. There were stampedes. The phone lines jammed with concerned calls. There were even more reports of terrible things, like suicides and angry mobs.

In retrospect, given that it was late in the year 1938, maybe there was already some tension hanging around in the air. News travelled very slowly at this point, but there were events already taking place on the continent of Europe that must have been unsettling to learn about. Maybe people were already on edge a bit.

This radio broadcast changed the fate of Orsen Welles; it was about to make him a super star. At the same time, completely unknown to the creative radio teleplay writers at the time, but history was about to be made.

A critical lesson was forged about how to write for the medium of radio.

An entire stage filled with actors, each with their own microphones. They had their script in hand, which they had rehearsed and worked on for maximum dramatic effect

There was a live orchestra, who played the opening theme song music, and then their job was to provide the live sound effects to help convince the audience of the authenticity of this experience….think about doors creaking open, explosion sounds, and eerie bass sounds to scare you. Those were all created by musicians using different percussion instruments (and sometimes the actors as well as foley sound)

The job of the musicians was to make it all sound realistic, but the assumption was that the audience would still not actually believe what they were hearing…it was the dramatic step between the audience and the people

The pacing of the show was also meticulous…drag out the beginning moments, add more music to increase the tension, and allow for the pacing to speed up as the story unfolds.

If you were to receive a brief as a podcast producer today, for either a dramatic show or a non-fiction show, I would bet that almost all of the same aspects listed here would be what your job description is.

Trade “rehearsed” for edits. Swap orchestra for soundlibrary. Substitute live foley for sound engineering.

But keep dramatic steps. Keep tension. Keep pacing. And keep the experiments.

And what you’re left with is a fuzzy line in the history of podcasting. And a historical event that still teaches all those folks making podcasts today how to do it well.

Thanks for finding Bingeworthy, a listener-supported newsletter. If you’re aligned with my goals: To bring narrative podcasts out from the fringe shadows; To make them a subject of critical discussion; To see them recognized as their own storytelling format….please support this publication by purchasing a subscription. There’s an alluring discount available now.

It was, not.