Behind Closed Lips: Delving into Two Journalist-Driven Tell-All Podcasts, Absent the Subject's Narrative

A closer look at how Believeable: The Coco Berthmann Story, and the hit podcast Scamanda, unravel the truths and the lies of a life story when the subject is not there to speak for herself

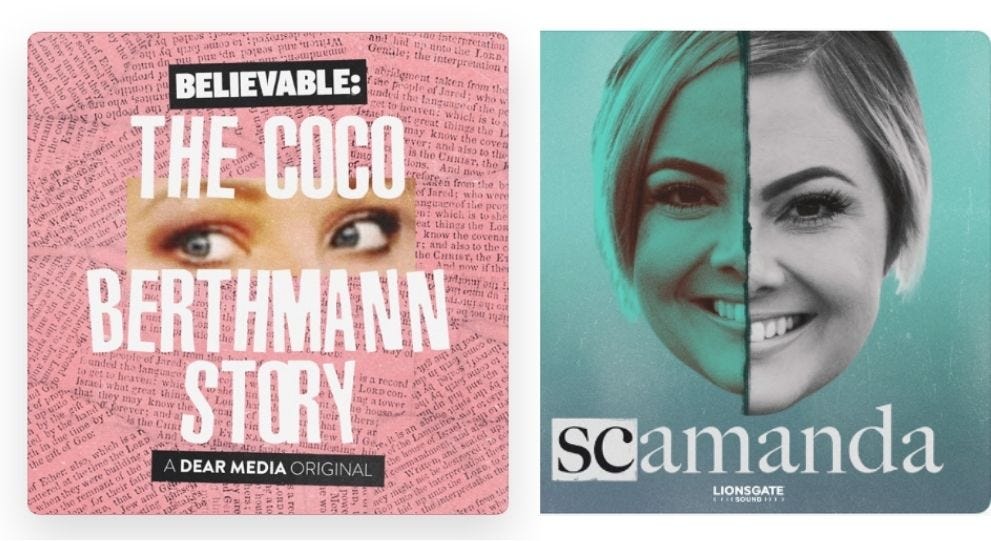

It was odd last summer when two podcasts about women faking cancer landed on the Internet at basically the same time. Both were about young women who were connected to Evangelical Christian communities. Both claimed to need help to raise money for “alternative treatments,” and “essential things.” Neither story featured the accused, the subject of the investigation, to speak for herself.

Scamanda, for those who haven’t listened to this blockbuster hit, is part salacious coverup story, part hardboiled detective yarn. It explores the layers and folds of the story of Amanda Riley, an American woman from Northern California who faked cancer (and a range of other horrible things) to leverage generous donations to fund her lavish lifestyle.

The other series, Believable: The Coco Berthmann Story, is about a young woman from Germany who landed in an LDS community in Utah as a Nanny. Eventually, she had her own cancer story, but that’s not what made her famous. Coco’s origin story was that she was she claimed to be a survivor of child sex trafficking. I’ve written here before about this series, as the first usage of an AI voice actor in a narrative podcast series, but today I’m here to talk something different.

Normally, I wouldn’t dwell on any one series for so long

But the production choices, the approach to journalism, and the general tone of this show made me swerve back to the Coco Berthmann series, even when it veered past the 10-episode mark.

There were three compelling reasons for this, and I’m going to lay them out for you here today, while I contrast them with the different production choices made by the series Scamanda.

And then, stay tuned, way down below you can find the Q+A Zoom session with Host and Producer, Sara Ganim, and Showrunner, Karen Given, at the bottom of this post.

1. Please call us…no really. Call us.

You’ve heard this countless times: “So-and-so declined our request for an interview.” Or, “On multiple occasions, we reached out to X for comment, but did not hear back.”

These statements are the peanut butter and jelly of investigative podcasts.

However, it’s a fact of journalism, and also maybe humanity, that not everyone is ready to speak their truth to the world via worldwide radio waves. Mind the gap: the journalists can take it from here.

What I will explore here is how these journalists dealt with the silence; and then, how this silence reads into the listening experience.

One thing to say upfront is that if don’t hear a disclaimer for the subject not appearing in an investigative show, it should immediately throw up a red flag. That's just not what good journalism does.

Both Scamanda and Coco make attempts to go back to the sources for comment or contribution. Neither subject agrees. However, the way both shows deal with the subject’s absence creates nuances.

One important nuance of Scamanda is that there’s actually a third character: the journalist Nancy Moscatiello. She spent years investigating and documenting the inconsistencies in Amanda’s stories. Her sister died of actual cancer during this time, and she’s also personally sued by Amanda for defamation for investigating this exact story (Nancy won this fight).

Moscatiello is part hardboiled detective who offers evidence and gravitas to the story, and part journalist/investigator who meticulously outlines the facts. This tone sometimes stands in contrast to the main narrator, British broadcaster Charlie Webster, who is an award-winning journalist herself and did some of the digging for this series. But if you listen closely, this was Moscatiello’s story first.

Yes, they called and texted and emailed the subject, Amanda Riley, for comment. No, she did not comply. But in the absence of that, and given the surplus of personal court documents, I did get the feeling that the two investigators, Webster and Moscatiello, came to their own conclusions.

In many ways, the Coco series is in the same boat…it’s also a story that’s investigated by seasoned journalists, and they are forced to come to their own conclusions when they can’t speak to the main character directly. But the key difference is that Nancy had skin in the game; she had already been dragged through an expensive and stressful defamation lawsuit. Journalist first, but the role of defendant was a close second.

Scamanda became a runaway hit this summer, topping the charts of most services. At some point, I noticed that a number of new bonus episodes began to appear. These were no longer slickly-produced episodes, but talkies between Webster and Moscatiello, as they poured over some new detail of the case, or had a conversation with a new source who came forward.

I listened to these episodes as they were released, but I couldn’t help be feel that it had all become a bit…gossipy…and sallacious. Faking cancer is so bad that you can’t not look at it. I don’t fault them for leveraging the popularity of the series—evidently, people loved it. Great that they made a hit series.

But when I began to feel like I was reading a smutty paperback romance novel in the aisle at the drugstore, I thought it was time to take stock of this moment.

Truthfully, the Coco series began to make me feel like this as well, in or around Episode 6. But the difference is that they changed lanes.

To begin with, they actively sought out her participation throughout the series…as in “Coco, if you’re listening, we still really want to hear from you…” In fact, the whole series ends on the note that they had not given up on the idea that she might still call; the series may, or may not, be over.

To find out if she called, read on to find the Q+A below on this very matter.

There’s a difference between:

Call me, if you dare.

And:

Please call me. Actually do call. We are waiting for your call.

And the upshot of all of this leads to my second point.

2. Coco switched lanes from gossip to a conversation about mental health

It’s not normal to fake cancer. The lengths that you have to go to to be successful with this ruse are dramatic. For Amanda, it might have involved injecting terrible (otherwise life-saving) drugs that she did not need.

But faking that you’re a survivor of child sex trafficking is a whole other thing.

As a journalist, this is a part of the story that you really don’t want to get wrong. Even if some small part of that story is true, nobody wants to be the person who calls it out as a lie (and get that wrong). Even if it’s a partially fabricated story, there are about six zillion layers to get through, each one more confusing and contradicting than the previous.

As I rounded the corner into Episode 6, I will admit that I sort of stopped caring about Coco. Was it true, or was it a lie? Both seemed like definite possibilities at that point in the story.

But then I wondered: Now what? I was slipping into a state of moral decline. Here I was, interloping in a story about an undeniably difficult childhood and I began to lose track of which details of her dramatic life story could be real and which were potentially fake.

Then came Episode 8.5. In a somewhat radical move, the journalists called an actual Psychiatrist, Dr Sahom Das, to get a “diagnosis” for this Coco person. Could she be lying about all of this? If she is lying, what does that mean about who she is? And who, actually, would make up a story like that?

Dr Das poured over the case files of Coco to come up with a “diagnosis,” which I’ll put in air quotes, because HIPAA laws are quite clear that patients need to participate for there to be a proper determination.

But what this production choice does for the series is quite profound. It immediately steered the narrative away from a titillating story about a potential sex trafficking survivor, to a conversation about the actual underlying issue: a mental health disorder.

It was a risky choice to make in some ways: for one, there are all kinds of medical ethics that get in the way. And two, there was no way to provide a clear answer here. And for three, it risked alienating the potential for Coco to actually appear in this series— if we took that potential seriously in the first place.

But as a listener, the reason why this worked for me is it changed categories; there was now a reason to have this conversation, and not just for clickbait reasons. I was ready to engage with this story on the level of a mental health struggle, and not a godsibb investigation about an unspeakable childhood trauma.

3. Team Coco employed a collaborative - perhaps a feminist approach - to production

When you listen to the Coco series, after a few episodes, you will welcome a new character into the storyline. Her name is Karen Given, and what you’ll notice is that she’s also one of the producers on this (very lean) production team. She’s the Showrunner, but also a producer and the sound mixer.

And now, she’s another journalist on the mic to help us sift through fact and fiction.

If you read the Q+A below, you can find out the backstory of how this came to be. But the short story is this was an honest choice.

If you work in production, I don’t have to tell you there’s a politic behind who gets which production credits. But there’s an even bigger politic, along with many practical choices, about who actually appears in a series, in front of the microphone.

The cutting room floor is where most extra voices end up. A story always needs to be tightened; an audience can only connect so many voices. But the other reason is that the narrator needs to have the authority to tell a story. If you limit that authority, it can limit the potential of this story to connect.

So when I heard Given’s voice in there for the first time, I couldn’t help but think: this is an interesting choice. I surmised that we heard her once, she would need to stick it out to the end.

My hunch was right. Once she entered the story, she stayed in the story. I liked that she was there, she brought a new angle to the story, and they didn’t always agree, which brought new ideas to the table.

When I asked the two producers, Ganim and Given, during our Zoom interview why they made this choice, was clear, and twofold. First, It was an honest reflection of their work process. Second, Ganim loves a “process story.”

After one particularly challenging interview, Ganim called Given to talk about it, and as producers do, they recorded the conversation. When they listened back to the tape, they realized that this conversation was now part of the story. It had to be there.

To be sure, we have a very competent journalist as the narrator. Sara Ganim became the third-youngest Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist when she was just 25-years-old. And yet, she couldn’t do this one alone.

Producing is a group effort. But too often, the final look of the project has the visage that it’s a solo effort. What does it mean to openly admit, and then share the microphone, to bring your team into the mix?

We could call this inclusive. But something in me wants to call it a feminist approach; not because the term is a perfect fit here. But more because I’ve listened to so many series hosted by male narrators who don’t share the microphone to tell the story—even when it’s evident they aren’t they aren’t working alone.

Maybe feminist storytelling choices are willing to admit to the fact that these stories aren’t built alone. It’s not just one all-knowing producer/journalist/host that goes away and solves the case by themself. This approach also reminds me of Bone Valley, where Gilbert King pulled Kelsey Decker into the story, instead of leaving her as the voiceless junior reporter (ergo it’s not just women who can make this choice).

These complicated stories are made by teams of people. And when it makes sense to share the microphone to help get the story out, I appreciate when this is done with honesty. It makes it an honest process.

Curious to listen to this series?

The following is an excerpt from a Zoom interview with Sara Ganim and Karen Given. It has been edited for clarity and length.

[Samantha Hodder]: Your season just wrapped…how long has it been that you've been working on this?

[Sara Ganim]: We worked on it for about a year. We started in September of 2022, and we pretty much wrapped in September of 2023.

[SH]: Were there always going to be 10? I guess there are really, technically 11 episodes. But was that always the case? Or did it just grow and grow?

[SG]: I didn't just grow and grow….Was it going to be 6? And then at some point, we knew that wasn't going to work. So we got approval for 10, and then [Dear Media] were like Absolutely No More! But we needed to build in a bonus because we were behind in production.

So the bonus episode was going to be just us….but then we did this interview with [Forensic Psychiatrist] Sohom Das [which became episode 8.5], and we decided the bonus should be him.

[SH]: I’m curious about the origin story of this series, I realized that Coco herself had been on the Dear Media flagship podcast The Skinny Confidential, so they had an invested interest in the story.

Who pitched to whom, and then how did the two of you come together to make this series?

[SG]: I first time I heard the name Coco Berthman was when Dear Media reached out to me and asked me if I would consider doing the project.

Jocelyn Falk who at that time was VP of Originals at Dear Media. We know each other from her work at HBO when we made the movie Paterno together, which was based on my reporting [about the Jerry Sandusky child sex abuse report, which led her to win a Pulitzer Prize for local reporting].

[Karen Given]: And for me it was this pretty similar thing I had never heard of Coco. But I've done a previous Dear Media project. And so they reached out to me; Sara and I didn't know each other didn't know each other, so we really started from scratch.

[SH]: When I get to the end of the series, I often go back, and I listen to the first episode all over again. And when I got there I realized, wait a second. You kind of told me the whole story right at the beginning.

So I want to hear from a storytelling craft perspective, why you chose that approach, and technically, nerdily, when did you write Episode 1?

[KG]: So we always knew that Episode 1 was going to be Episode 1.

I think it was a very conscious decision that we wanted to start the story that she was telling and how big that was. We actually wrote Episode 1 relatively early on. Some of the those were the interviews we got ahead of time, and it was done-done done before we even started Episode 2; it was the first one in the can by far (months).

But it was a very conscious decision. We felt like you needed to be introduced to Coco. You needed to understand the platform that she had, and how widespread it was. I think a lot of people hadn't heard of her, so we wanted to sort of establish her level of fame before going back and trying to figure out if it was real.

[SG]: We also were were pretty conscious about creating teases and twists and elements of surprise. And so that presented a good opportunity at the end of Episode 1, the way that we structured it…at some point we were talking about setting it up as if she was telling the truth for a little bit longer than we ended up…that was in in an effort to create elements of surprise.

[SH]: Did that mean that much of the development, research and story editing was done by the time you wrote Episode 1? Because you really have the full arc of it in there…[you] lead us down the garden path for a while before we're yanked back and told what was really going on.

[SG]: I don't think it's accurate to say that we are done when we wrote it. We wrote [Episode] 1 because we're like, we’ve got to write something! We were really still in the thick of the reporting. And we felt like we had to start the ball rolling on production, or we were just going to be super late and blow past all of our deadlines.

One of the biggest regrets, and I think I can speak for both of us, is that we weren't able to do the reporting, start to finish, and then the writing, start to finish. We had to do them at the same time.

It didn't allow us to look at the big picture at any moment and say: How can we play with the timeline? How can we rearrange things? How can we make sure that were really specific and deliberate with the storytelling and the arc of the story? We just couldn't do that.

[KG]: There was a very interesting thing that happened with this podcast which hasn't happened with anything I've worked on before…people very much wanted to talk to us, and we wanted to talk to them.

But there were barriers, and we weren't able to get those interviews in when we wanted to. We knew what the story was, but we didn't have the interviews in the can yet, because we just couldn't get access to the interview subjects.

It wasn't bad planning. It was just circumstances that made us have a really strange production schedule.

[SH]: It's clear that you had a strong gut reaction to this story…it's a pretty gutting story in a lot of ways. But I'm wondering did your gut shift during the process of producing this over a year?

[KG]: I don't know that my, that our guts shifted. I do know that Episode 3 was completely rewritten at least three times!

We knew that we wanted Episode 2 to be the start of her public story, and the origins of her connection to the LDS community.

After I wrote [Episode 3], Sara looked at it and said: We're not ready for this. So we literally scrapped that episode. Then we recorded the interview with Becky Mackintosh and realized: This is Episode 3.

But that is not how I would suggest anyone figure out their episode structure! I teach this kind of stuff, and this is not how you do it!

But it's how it worked out for us.

[SH]: Sara, you went to Germany a couple of times…you met her mother…did your gut waiver, or did it say pretty strong?

[SG]: I think I feel like Karen could answer this for me better than I could answer it for me.

[KG]: I think Sara always had always felt that most of Coco story was probably not true, but always had that that thing in the back of her mind saying: But what if it is?!

[SG]: Most people are sort of in this camp of: Evil Lady Makes Up Entire Story.

But I felt like there was no nuance to that take; it's my experience that there is nuance even in really horrible stories.

I don't always have an empathetic approach, but I did feel like this was a story that was way more complex than what people were distilling it down to on the Internet.

Then it was impossible to figure out where the truth was. I do still believe that there's some truth in the stories that [she tells that don’t] ever come to light; because you can't ferret out all the stupid stuff she lied about.

It's just impossible. She did that. That was totally her doing. She did that to herself.

[SH]: She chose two pretty big topics: to claim that you're a child of sex trafficking…and then to claim you have cancer…it’s tough for journalists [to outright dismiss these]. Have we learned anything from the #Metoo movement? And the way the court system treats victims?

So to just dismiss it outright without diving into it…I think that you danced around some very dark subject matter pretty quite assertively here.

I'm curious about the backroom conversations between you two.

[KG]: Yeah, there there were [a lot of backroom conversations].

It was very important also from us for us very early on to have conversations with actual child sex trafficking survivors and center their experience. Because it's so easy to poke holes in specifics of Coco's stories that someone would say, Oh, look! She lied about having a sister named Anna, therefore she was lying about everything.

And that's just not how it works.

There are some real reasons why survivors might miss-remember things, or lie about things, or change their stories. And we wanted to be very mindful of that, so that was what was driving us to look for the complexity.

[SH]: Karen, at some point you also became a character in the podcast. Tell me about that creative decision.

[KG]: It it sort of became a way that we could drive the story forward and keep it interesting. Because if if we just wanted Sara to explain these very deep conversations that we were having behind the scenes, auditory wise, that wouldn't be all that interesting.

So it gave us ways to explore these complicated ideas and concepts in a way that is entertaining hopefully for the audience.

[SG]: I'm a huge huge fan of a process story. And mostly that's because I think when you eliminate the process, you lose a lot of the story, and I think that it was important for me.

If you take out all those process conversations and process scenes, then you do lose a significant part.

We all sort of ended up in the same place, but the process of getting there is a big part of the story.

It informed how we put it together, and I felt that if we took that out, it would be a big loss for the listener.

[SH]: I also took it as a bit of a feminist approach. A lot of podcasts give the hosts the all-knowing power, with craftily written narration tracks that bring it together. But the honest truth is that it was a group effort to pull the story together. It feels more honest this way for me.

It's a much more collaborative approach. It's not sort of this all-knowing host, narrator voice, who pulls it all together for you, and you listen to them 60% of the time in the story.

[SG]: We could not have eliminated these other people who [helped pull the story together], Karen first and foremost.

But then the German reporters Kirsten and Katarina…I could not have spoken for them. They did the actual work and and their perspective.

We don't all agree all the time; that perspective was important.

At the end of the day, we were on different pages about this [story].

Let's let our listeners hear both perspectives, because some people are going to be more in your camp, and some people are going to be in more in my camp, which is great….and that’s what I mean by a process story.

[SH]: I have to be honest… I was starting to feel, by around Episode 6, a little icky listening to this difficult story. I started to feel like: I don't know if it matters; I don't know if we should care.

Why are we dwelling on this person's fucked up life story, who is narcissistically trying to get my attention?

But then in Episode 8.5, when you spoke with the Psychiatrist, it veered from gossip to reality, and it gave it some gravitas. It actually made me care for the story all over again.

Can you give me some background about why you did that?

[SG]: We we knew we wanted to have that conversation. We didn't think it was going to be its own isolated episode. We were going to to kind of sprinkle it in the later episodes.

We knew we were going to bring that person on board to the team in like a consultant capacity, because we wanted that person to actually spend a good amount of time looking at documents and make a real assessment, not him just doing us a favor.

I called Karen immediately, like from the street outside the studio [after the interview], and I said: We can't just take sound bites from this. We have to use this conversation.

So we just like took that conversation to a higher level and convinced everyone [at Dear Media] that we would need one more episode.

[SH]: I think that the listener needed at that moment to continue with the story. It did break the [True Crime] format. But you're right; it needed to.

It went from being a kind of true crime investigation to something more along the lines of impact journalism, because it dove into the mental health angle of this story. And then it asked, from a professional perspective, whether or not this was all a lie, or partially a lie, or somewhat of a lie? Which then made it a mental health conversation.

[KG]: We always knew that eventually we were going have to discuss the mental health aspect of this story. And I think a lot of true crime podcasts don't go there.

There was just no way, after hearing about her background and her behavior, that we could ignore the mental health question.

[SH]: Any final thoughts on working in the AI capacity?

[KG]: I still love that we had an AI of Coco's voice, I still stand by that decision. I think it was great. I think there are lessons learned: people want to hear about [the fact that it was an AI voice] way less.

[SG]: Yeah, I second all of that.

I'm also just a big believer in being in the camp of trying new things in within news organizations and news on news projects versus being scared of trying new things, for a lot of reasons.

I get like flashbacks to the 2000s when everything started to fall apart. I attribute a lot of that to the resistance to embrace new technologis.

[SH]: The clips of Coco's voice that were Coco, that were were taken from Instagram, or her “Lives.” How does that work? From a legal perspective, she doesn't release them. They're on the Internet, but does that make them publicly available? Where where is the line in the sand?

[KG]: A lot of those were taken from the Dear Media podcast [which she appeared on]. So a lot of the clips that you heard were from, she did sign a release for that. Everything else that you heard was under fair use and was reviewed by a lawyer.

We had a lawyer who would tell us how long the clips could be, whether we had set them up properly, whether we had, you know, given proper credit to who we needed to give credit to all that kind of thing.

But in those cases what the lawyers concerned about is not Coco's right to that audio.

It's the source right to that audio.

[SH]: You leave the series at: Coco, call me anytime. Did Coco call?

[SG]: Coco has not called.

[SH]: Would this project have been different if she called? Would it continue, would it change, if she actually did call? Would you take the call?

[SG]: I mean we would take the call 100 percent. Would it change? I don't think so, unless something completely unforeseeable was said.

She has ruined her ability to tell the truth…she has no credibility. It's an almost unfathomable.

[KG]: We had a lot of conversations about would happen if she did call and consent to an interview. And I would always say, well, that we we pretty much have to make that Season 2, because anything she says to us would then have to be fact-checked. And we'd have to corroborate, because she has told so many lies that it really does become impossible to believe what she says.

[SG]: It's my favorite kind of stories where, like, you're going out and trying to figure out what's real and what's not. And sometimes you're more successful than in other times.

Once I came around to accepting that we just may never truly know everything that's real, I felt really good about where we ended up.